PRESS

New York Times

New York, New York

January 13, 2007

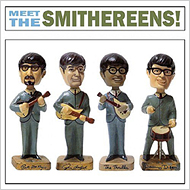

The Smithereens (from left, Dennis Diken, Pat DiNizio, Jim Babjak and Mike Mesaros)

have recorded their version of the Beatles’ American breakthrough album.

Interpreting the Beatles Without Copying

By ALLAN KOZINN

Published: January 13, 2007

Correction Appended

Lately I’ve been wondering why, as a more than casual Beatles fan, I’m not interested in note-perfect covers by Beatles tribute bands, even though, as a classical music critic, I happily spend my nights listening to re-creations — covers, in a way — of Beethoven symphonies and Haydn string quartets. What, when it comes down to it, is the difference?

Obviously, this is something of a comparison between apples and oranges: we first heard the Beatles’ music on their own recordings, whose sounds are imprinted on our memories and are definitive. Our first encounters with, say, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony were through performances that, however spectacular, have no direct link to Beethoven himself. Yet Beethoven’s score of the work is a detailed blueprint of how he expected it to sound, and any performance will be governed by that, allowing for interpretive leeway that may be subtle or dramatic. A cover band, hoping to reproduce the original recording, has less flexibility.

But a new album by the Smithereens shows how much interpretive leeway a rock band can have, even when it intends to perform faithful covers. The disc, “Meet the Smithereens!” (Koch), which comes out next week, reproduces the track lineup and, to a great degree, the original arrangements (at the original tempos and in the original keys) of the Beatles’ 1964 American breakthrough album, “Meet the Beatles!” But it does more: the 12 songs are filtered through the Smithereens’ own crunchy New Jersey bar-band sound, a quality likely to come through even more strongly when the band plays the album live at the B. B. King Blues Club and Grill tonight.

The Smithereens made their name playing their own material, but they have recorded Beatles songs before, and they have always had a soft spot for the concision and zest of British Invasion bands. So they approach this music as fans who know it intimately, but also as composers who know what makes a great song durable.

They are hardly the first to cover a complete Beatles album. Big Daddy recorded a doo-wop version of the full “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” in the early 1990s. Phish released a live performance of the complete “White Album” in 1994. In the late ’80s, the Slovenian art-rock band Laibach released “Let It Be,” a ponderous, reordered version of the Beatles’ album of the same name, albeit without the title track.

What makes “Meet the Smithereens” unusual is the degree to which, like a good classical performance, it balances fidelity to the original with a projection of the interpreter’s style. Typically, Beatles covers and pop covers in general are an interpreter’s art and emphasize the performer’s vision. After all, if you don’t have a distinctive perspective, even one as off the wall as Laibach’s, why should someone listen to your version instead of just playing the original?

Tribute acts, by contrast, are purely recreative. Their goal is to reproduce a band’s music rather than to make their own mark on it. The Smithereens acknowledge this world without quite joining it. These days, everyone from the Grateful Dead to R.E.M. has its own shadow specialists. But Beatles tribute bands have long been a global industry.

Many, though by no means all, borrow a page from the Elvis impersonators’ playbook and turn their performances into theater pieces. They dress up in period costumes, changing from short to long wigs, moving from collarless jackets to psychedelic outfits and affixing paste-on beards and mustaches as the show progresses. And they imitate the Beatles’ accents and jokey patter. (A band that takes this approach, 1964 the Tribute, is playing at Carnegie Hall on Jan. 27.)

I’ve never understood the appeal. When I saw “Beatlemania” on Broadway, in the late 1970s, I admired the stage band’s skill, but left the theater feeling I’d have been better off listening to the records and paging through old Life magazines. And watching other faux mop-tops trading on Beatles nostalgia over the years, I’ve always felt a little embarrassed for the musicians, who had clearly devoted significant effort to learning arrangements that in some cases were too complex for even the Beatles themselves to perform live, yet who were sublimating their personalities (and musicianship) to the business of role-playing.

Which is not to say that what they do is without merit; quite the opposite. For anyone who has listened closely to how the Beatles’ vocal and instrumental arrangements work, it’s hard not to admire the musicianship of bands that reproduce it accurately. Still, you could argue that at least some of the Beatles’ music — recorded layer by layer, carefully polished in the studio, and using tape loops, backward sounds and other innovations — is actually electronic music: the recordings are the score and the performance, self-contained, just as much as a tape work by Stockhausen is.

Even so, those recordings can be transcribed fairly precisely, as Tetsuya Fujita, Yuji Hagino, Hajime Kubo and Goro Sato demonstrated in “The Beatles Scores” (published by Hal Leonard in 1993), and those transcriptions can be learned and recreated live with startling exactitude, just as the score of a Shostakovich symphony can. And Glenn Gould’s manifestos about the death of the concert notwithstanding, there will always be something electrifying in a live performance that cannot be captured on a recording.

That live experience is something tribute bands offer that can no longer be had from the Beatles themselves (although Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr still perform their old hits on tour). For that matter, tribute bands offer something — quite a lot, actually — that the Beatles never did. Between late 1962 and the summer of 1966, the Beatles recorded 118 songs. But during their international touring years (starting in late 1963), they played a mere 33 songs in concert. The last album from which they played any material live was the 1965 LP “Rubber Soul”; thereafter, they recorded another 100 songs on six albums. With technology far beyond what the Beatles had (sampling keyboards, in particular), tribute bands can play them all.

That said, when a string quartet plays Haydn, it doesn’t set out to produce an unvaried copy of what’s in the score. The players make interpretive decisions about tempos, balances and tone color; ideally, a quartet’s reading will breathe differently from night to night, and will be distinct from a competing ensemble’s account. And except for the occasional misconceived children’s concert, quartets don’t don Haydn-era wigs and costumes, or adopt Austrian accents.

This is what I like about “Meet the Smithereens!”: it bridges the extremes of note-for-note fidelity and pure interpretation, offering the best of both worlds. The band has treated “Meet the Beatles!” as a symphony, a complete cultural artifact, to be heard intact. It barely matters that “Meet the Beatles!” was not quite the album the Beatles intended, but rather a compilation made by Capitol Records, using 9 of the 14 songs from the group’s British album “With the Beatles,” as well as three songs released as singles. For American listeners who discovered the Beatles at the time, as the Smithereens did, “Meet” has an emotional resonance that “With” does not.

The arrangements on “Meet the Smithereens!” have all the vibrant energy and directness of the originals, and even minor details like the keyboard glissandos in “Little Child” and the overdubbed handclaps on “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “I Saw Her Standing There” are faithfully preserved.

Yet you wouldn’t mistake it for the Beatles, as you might with a tribute band. If Jim Babjak’s guitar solos follow the contours of George Harrison’s, they aren’t slavishly identical.

Where the Beatles moved to acoustic guitars for “Till There Was You” — the only cover on “Meet the Beatles!” — the Smithereens opted to keep it electric, with a touch of distortion, and to abandon the saccharine quality that Paul McCartney brought to the vocal.

The guitar tone and effects, and the way the vocal harmonies are balanced on, for example, “This Boy” and “Hold Me Tight,” are the Smithereens’ own. And so are their accents. The album manages to scream Beatles 1964 and Smithereens 2007 all at once.

Correction: January 18, 2007

A music column on Saturday about a new album by the Smithereens (“Meet the Smithereens!”) that reproduces the song lineup and much of the arrangements on “Meet the Beatles!” misidentified the Smithereens’ lead guitarist, whose solos were compared to George Harrison’s. Although Pat DiNizio does play guitar in the band, it is Jim Babjak who plays lead.